Let's get intense about yeast

a TL;DR guide to the science, history, and witchery of yeast in winemaking

Hey nerds!

Sorry it’s been a while. Turns out working a 60-hour week (wine job + day job) doesn’t leave a lot of room for substacking - who knew! The other day, I was thinking about the wine obsession honeymoon phase and the topics I wish I had stumbled upon sooner. Which brought me to yeast :)

When you google natural wine, you’re likely to find 101 articles titled something like ‘to sulphur or not to sulphur’. Tbh, I think the sulphur debate is tired. Natural wine is so much more than a no (or low) sulphite product. When we anchor ourselves to the sulphur debate, other equally important aspects of the wine-making process get lost. Aspects like yeast.

I’ve noticed this first-hand when pouring glasses and offering scatty definitions of natural wine. People often ask, ‘natural wine has no sulphur, right?’ but they’ll never ask ‘natural wine uses native yeast for a spontaneous fermentation, right?’. How strange. Perhaps it’s down to the fact that sulphur additions are a slightly simpler concept to grasp. But I think it’s more to do with the fact that we stop the conversation at So2, and leave yeast out of the picture completely. So let’s get into it, shall we?

What is yeast?

Wine = fermented grape juice. So, how does the grape juice ferment? That’s the job of yeast!

Yeast is what turns the grape juice sugar into alcohol (and produces carbon dioxide and some other byproducts too). Fermentation was a bit of a mystery until 1857, when Pasteur demonstrated that yeast weren’t just passive participants — they were the very cause of fermentation. Now, there are two main types of yeasts used in winemaking:

Native Yeast - these creatures exist on the skins of the grapes, in the vineyard ecosystem, and in the cellar. These yeasts are relied on to kick-start a spontaneous fermentation. *Note in a spontaneous fermentation loads of different yeast strains are at play (as many as 20-30 according to wine science lord Jamie Goode) and more than 350 strains have been formally identified globally.

Cultured Yeast - these are cultivated yeasts added by winemakers to produce a more controlled fermentation - called an innoculated fermentation. Here, specific yeast strains are selected to achieve specific flavours or characteristics, like more acidity in a particularly hot year. Speaking generally, most commercial wine that ends up in our supermarkets are made with cultured yeast. *Note most cultured yeasts were ‘wild’ yeasts at a point in time; they’ve just been individually selected and added because of their properties.

Now, if you’re wondering what ChatGPT offers when you ask her for a yeasty girl gang, here you go…

*moody brett is pretty accurate tho

An oversimplified history of yeast and winemaking

The rise of selected yeasts

Obviously, wine making started way before the 20th century, but I’m going to start here because I think it’s really interesting. At the turn of the century, scientists began to identify specific yeast strains that were the most effective and reliable for fermentation. These selected yeasts were first sold in liquid form in the 1920s, and by the 1960s powdered dried active yeasts (DAY’s) dominated cellars across the world. Before these developments, almost all wine was, by default, fermented spontaneously. Nowadays, the opposite is true. Things changed pretty dramatically, pretty quickly….. classic.

These selected yeasts are marketed to winemakers as tools to produce the most amount of wine with the least amount of drama. The worst drama is a stuck fermentation, which leaves you with a partially fermented wine that is high in residual sugar, low in alcohol (because all of the sugar in the juice didn’t ferment) and is vulnerable to bacterial spoilage. That’s why opting for an ‘efficient’ strain of yeast that can get you over the finish line is a decision made by many in modern winemaking.

Nowadays, there are loads of strains that can be used for certain flavours or traits. The main golden boy of these strains being Saccharomyces cerevisiae (let’s just call him Sacchi). Sacchi is often selected as it’s quite resistant to alcohol, which means it runs ahead of other yeast strains when alcohol starts to rise in the fermenting juice. This means when winemakers pour a packet of Sacchi into the juice, there’s not a lot of room for more soft-spoken yeasts to do their job - particularly at the start of the fermentation where they often lead the way.

Whereas, in a spontaneous fermentation, numerous soft-spoken yeasts work together, until alcohol gets up to about 4-6% which is when Sacchi takes over. In this way, it’s not that Sacchi doesn’t play a role in spontaneous fermentations - it just plays one role as part of a much larger team.

The resistance

Now, after a fair few years of observing inoculated fermentation gaining in popularity, Jules Chauvet and his mates in 1970’s Beaujolais started steering clear of using selected yeast and other additives in the cellar. This is what many pinpoint as the start of the ‘natural wine movement’. It’s important to mention here that instead of carelessly mushing up some grapes and seeing what happened (as some people like to describe natural wine as) these guys and gals took it upon themselves to study the native yeast strains and their activities under the microscope, just as is done under inoculation. It wasn’t about doing ‘nothing’, it was about letting native yeast lead the way, maintaining a light touch, and intervening only if necessary. Hence, these folks advocated for a more observant approach to winemaking - utilising the diversity of yeast as opposed to diminishing it. This was pretty rogue at the time, and pretty at odds with the precautionary approach that was dominating modern winemaking.

Spontaneous vs. inoculated, does it really matter?

Now, where things get interesting for me is the importance of yeast activity in terms of more than just getting a fermentation over the line. Over the past decades, we have been developing a far more nuanced understanding of how yeast contributes to the flavours, texture, and individuality of wine. In a spontaneous fermentation, up to 20-30 yeast strains could be at play - taking turns keeping a fermentation moving. This diversity is often claimed to add depth and complexity. But why?

One argument is that relying solely on native yeast produces a slower fermentation, which is said to ‘blow off’ fewer aromatics. At first, I thought this sounded slightly vague and intangible, but I found a fun study to illustrate the point. Please take a look at this overly complex plot from Chen et al (2022)….

Let’s focus on the red lines. You can see that the total sugar of the spontaneous fermentation (the SF line) reduces more gradually across the first 10 days of fermentation than the total sugar of the two inoculated fermentations (XF and CF - both Sacchi led fermentations). Same story for ethanol in blue, but obviously in the opposite direction (as sugar does down, alcohol goes up). Long story short, spontaneous fermentations are slower, especially in the first 10 days or so.

Now, this study also showed that the spontaneous fermentation had significantly more yeast strains than just Sacchi working, and the activity of these yeast strains resulted in wines with more microbial complexity - more C6 compounds and acetate esters. So long story short; spontaneous fermentation = more yeast diversity = more microbial flavour compound diversity. Now, one study isn’t everything, but these findings help add weight to the claim that spontaneously fermented wines taste more complex and nuanced in their flavours.

Another point I want to make here if I may, is that studies like this are really hard to do but equally important to undertake. Without them, we really can’t really know whether the yeast activity itself influenced the flavour of the wine, or whether it was one of countless other uncontrolled factors like soil type, fermentation vessel, or even weather on the picking day, that led to differences in the resulting wine. Therefore, when comparing the spontaneous fermentation to the inoculated fermentations, Chen and friends used the same grape variety (petit verdot), from the same plots, picked at the same time, and fermented in the same vessel. In real life, this does not happen. So extrapolating from real life can be pretty anecdotal. Correlation does not equal causation, am I right? Okay, I tried not to get into the causation wormhole but I lost control sorry…

Yeast as a marker of ‘terroir’?

Wherever you may be on your wine dweeb journey, you’ve probably come across the term ‘terrior’. There are too many definitions out there, but it essentially refers to wine having a ‘sense of place’, such that it reflects the unique soil, landscape, year, and winemaking culture in which it’s produced. Many winemakers now see native yeast as a critical part of this terroir. As Nicolas Joly (hype winemaker I cant afford lol) says 'natural yeast is marked by all the subtleties of the year. If you have been dumb enough to kill your yeast you have lost something from that year'.

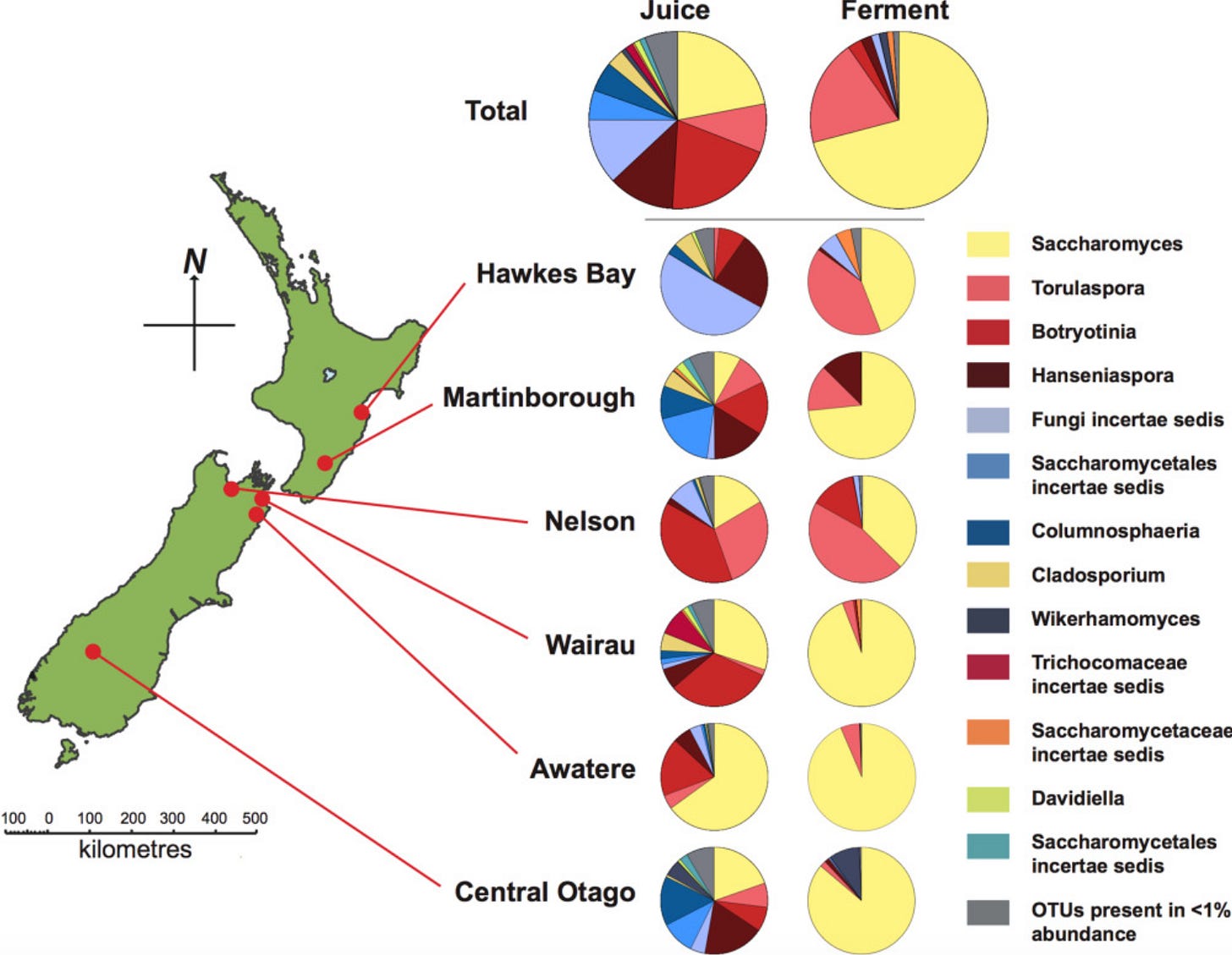

Native yeasts are also believed to play a big role in expressing vintage (or year-to-year) variation and site (place-to-place) variation. As non-sacchi yeasts are more likely to be found on the skin of the grapes and in the environment, they change more from year to year and from vineyard to vineyard. Therefore, relying on these yeasts to lead the fermentation is said to bring more individuality to wines produced. Putting some stats to these claims, a 2011 Kiwi study demonstrated that spontaneous fermentations were indeed dominated by the native yeast strains found in the vineyard - not just Sacchi. Later work also showed that these yeast strains were not only coming from the grapes and vines themselves, but uncultivated aspects of the environment like; tree bark, flowers, and the surrounding forests. So yes, you can sort of say that you can the local bark (yeast) in your spontaneously fermented pinot. COOL!

They also identified specific and region-specific yeast ‘communities’ - backing up the claim that spontaneous fermentations help to express locality. Looking at the pie charts below, you can see different areas in NZ have quite different makeups of yeast and fungi (for example Hawkes Bay and Awatere are wildly different). Even the areas close together - Nelson and Wairau - showed significant differences. aha terrior! science! yay!!

A final note on the ricochet effect of chemical farming

Decisions made early on in the wine-making process can have a powerful ricochet effect. First, the more chemical farming is used when growing the grapes (aka spraying herbicides, pesticides or fungicides), the less native yeasts are bound to survive on the grapes and in the environment. This means it will be harder to (or even impossible) kick-start and maintain a fermentation without adding cultured yeasts once you start stomping your grapes.

Second, if sulphur is added during grape crushing to protect the must, as a precaution to prevent bacteria from infiltrating, Sacchi takes control of the fermentation as it’s less sensitive to S02. Which is also why many winemakers rely on him if choosing to sulphur the must, as native yeast may not have what it takes to withstand a hearty dosing.

Finally, the use of these chemicals on winemaking equipment can also diminish the diversity of yeasts living in the cellar, which play an important role in getting a fermentation going. It’s not just about the yeast on the grapes — the cellar is a living ecosystem that brings lots of yeast to the barrel (bad pun intended). So TL;DR; everything basically affects everything in winemaking. If you opt for chemical farming or additives early in the process, you most likely have to rely on cultured yeasts later down the line.

Ultimately, using native yeasts over cultured yeasts is neither right nor wrong. It just matters what you're aiming to achieve. Yes, relying on native yeast comes with significant risk and requires a lot of work in the vines - it may take some years to build up your native yeasty girl gang after a chemical farming regime. But it’s hard to argue that spontaneous fermentations don’t result in wines with more individuality and character. IMO, they’re wines that can take you by surprise even after you feel like you’ve tried every niche varietal from every niche corner of the planet. I don’t know about you, but that’s what keeps me spending so much of my disposable income on these bottles and my Friday nights writing stuff like this.

So next time you find yourself casually discussing the concept of terroir in the pub with your mates (no??) don’t forget to throw yeast into the mix. She deserves to be part of the conversation.

If you enjoyed these yeasty rambles and want more, these guys know way more about all this than I do:

Yeast - wild, cultured, genetically modified - by Jamie Goode

Jamie Goode: Can we talk about terroir if cultured yeasts are used?

Xoxo Kristiane

Excellent article. Wrote one on the topic myself a little while back. What’s interesting to note is that non sacch strains still play an active role in inoculated fermentations so while commercial yeasts certainly impart their own characteristics to a wine, the terroir effect is not necessarily lost entirely. There are also some commercial non sacch strains out there that are being experimented with, selecting for specific strains that reduce the overall abv potential of the must (largely by converting sugars before sacch c. gets a hold of it). A topic that deserves a lot more attention for those that wonder why wine tastes like it does.

Very cool and awesome explanation. One thing I still don’t understand - why did chat make the girl gang a bunch of dogs? Lmk.